A followup to my Overton Window post – see here.

In video games, such as my favorite, Super Mario Bros, there are levels: stages of incrementally increasing difficulty you must chronologically pass through in order to progress in the game.

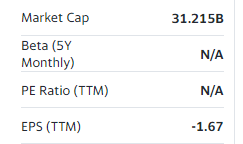

In investing, specifically in company valuation metrics, there similarly exist these “levels”. In recent years, as Silicon Valley startup darlings have taken over markets, it seems as if the game creators have updated the game with more levels. Long gone, it seems, are the days of simply searching for “Intrinsic Value” and investing in companies that generate “Free Cash Flow”. To be fair, Old Man Buffett is probably on the more conservative side. But still, when was the last time you heard the words “P/E ratio”?

|

| See above: Lucid Group, Inc. ($LCID), an EV startup. What is a good P/E ratio for an electric car company, one might ask? Many such cases. |

At the time Amazon was founded, a main gripe of its detractors was that they would be putting their money in a company that was “pre-profit” (AKA Losing Money). A mere quarter century and +$1.5T in AMZN’s market cap later, it seems like “pre-profit”, “pre-revenue”, “pre-customer”, and even “pre-idea” (okay maybe I’m exaggerating) are "pre-requisites" (haha) a company must meet, in order for an Legendary Partner (LP) at a Venture Capital Fund to invest in them. Currently, in corporate finance, the three main valuation methods used (DCF, precedent transactions, and comparable companies) commonly rely on a seemingly middle-ground Enterprise Value/EBITDA multiple to value companies. Yet, in the absence of EBITDA, some tech companies and startups have gone from a relatively tame “EV/Revenue” to now trading off "multiples of forward ARR" (next year’s expected annual recurring revenue), or "multiples of bookings" (SaaS contract commitments), or even "discount-to-ultimate-value" (X% of market leader's market cap as a base case)… wait what??

Naturally, as access to actionable investment information becomes more uniformly accessible to all, it makes sense that investors scour the lands to find potentially world-breaking and uniquely innovative companies (the Google of Web3 (what does that even mean)) as early as possible, to get in at a cheaper price (see Overton Window). The search to find these 100-baggers1 is a grueling battle only Peter Thiel’s strongest warriors can endure, making their very own Holy Crusade from Sand Hill Road to downtown SF to dole out term sheets to “founders” (ex-Stanford, ex-FAANG, sometimes ex-McKinsey in their LinkedIn bios).

Certainly, all this is not to say that being “pre-idea” necessarily makes a company bad, nor does being “profitable" make one good (see Enron2). As technology advances, and investors become smarter and more capable of identifying moonshots earlier and earlier, it is inevitable that more derived “levels” of valuation arise and slowly become the norm. All the more power to investors who are able to make successful investment decisions with less information to work on. I only write to hopefully discourage this from happening:

As we stray farther and farther from GAAP every day, Benjamin Graham is no doubt rolling in his grave. But as the investor’s metaphorical Overton Window moves, perhaps different multiples or levels are needed as new measurements for a new world... until they aren't. That's all to say: there’s levels to this.

Notes

1. “100-bagger” is a term used to refer to an investment that appreciates 100 times in value, often used by venture capitalists and investors to pat themselves on the back for an impressive investment

2. Enron infamously claimed it was profitable (net-profit), while in reality they were committing massive accounting fraud, using offshore accounts to hide significant losses and liabilities from their financial statements. Even with fraudulent Net Profit numbers, it's hard to fake cash flow. See below:

References

1. https://tomtunguz.com/time-to-disrupt-incumbents/

2. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bKoa5xGwtJk